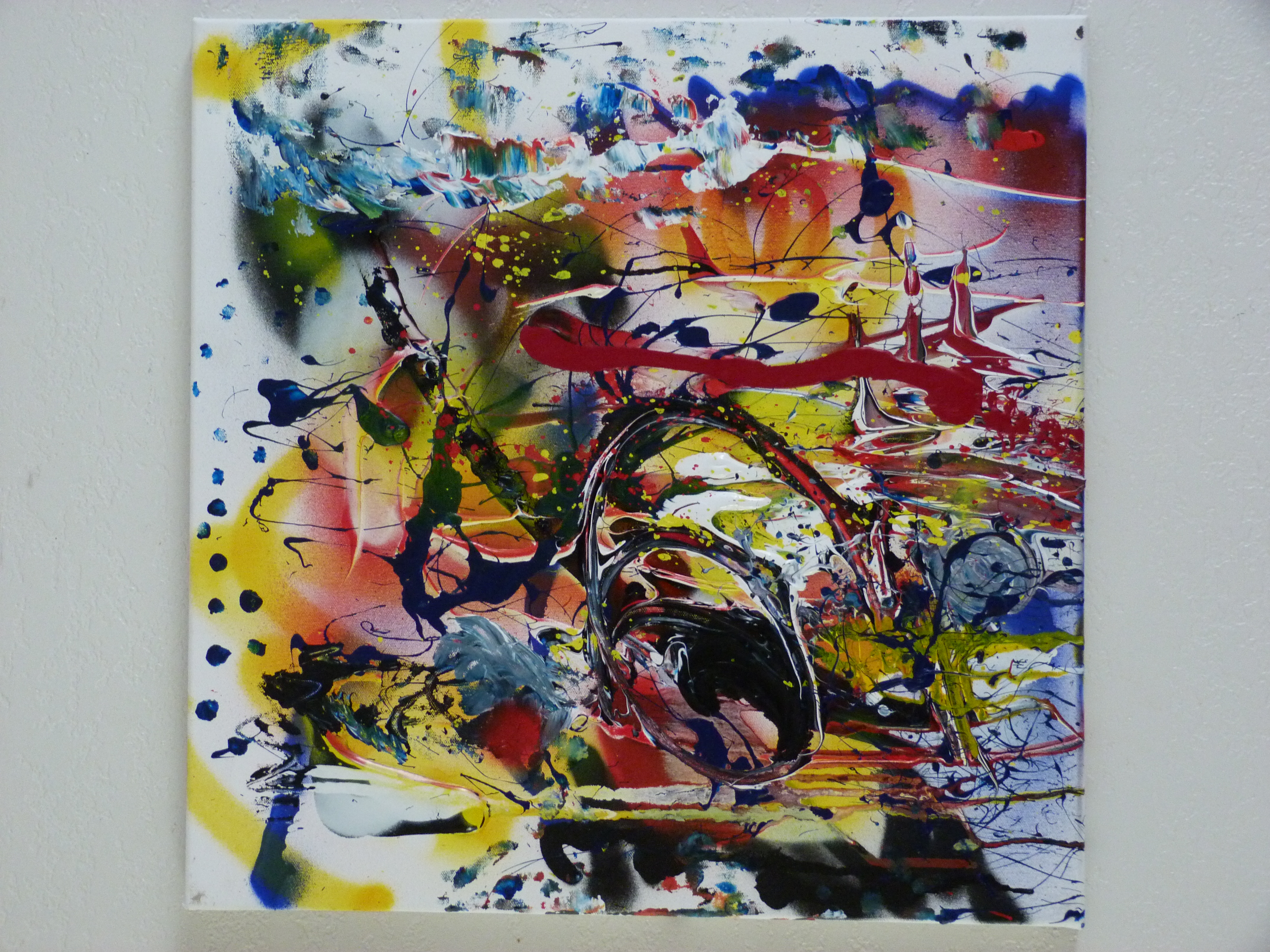

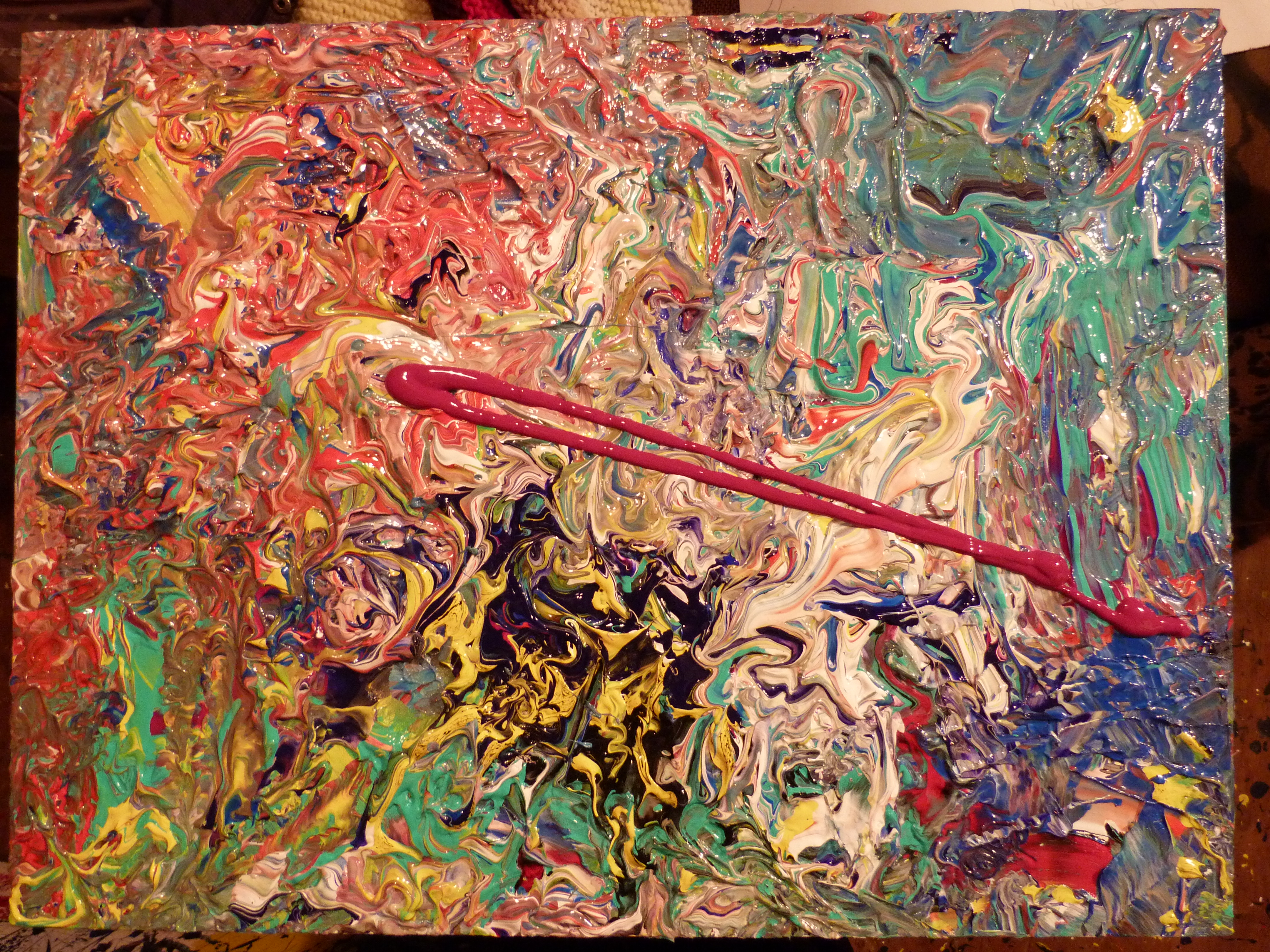

Fiction by Patrick Fealey ∑ Art by  Andy Lawson

Andy Lawson

down by the nightmare, the smell of burnt leaves hangs over the bank. it’s yesterday spoiling our dreams. the dead are never fully digested, just as the beautiful are never fully ignored. i was staring at the starer. the starer stared back. the wall was the best. it was blank and white and hurt less than colors and wallpaper patterns. i was pretty sure this meant i was insane.

YEAH, IT IS FUNNY HOW A MUSTACHE ISN’T ALWAYS WHAT ONE EXPECTS. I SAW A BARE-FOOTED BLACK HONDA STRETCHED OUT IN THE TREE-TOPS. I TOOK SIX SHOTS BEFORE I REALIZED IT WAS DEAD AND I COULDN’T EAT IT. AND HERE WE GO, THE HEDGER IS AT IT, ALWAYS AT IT WITH HIS SHEARS AND DUST MASK. ROBBING THE TREES OF THEIR LEAVES WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM BLACK & DECKER AND THE ELECTRIC COMPANY’S IN THERE TOO, IN ON A PIECE OF THAT AESTHETIC OF STRAIGHT BRANCHES SQUARED AND FLAT LIKE THE WORLD BEFORE COLUMBUS. I MUST LIVE ON A REGRESSIVE STREET. WHERE ARE THE ANGELS WHEN INSANITY ABIDES LIKE THE SEA? ROLLING COMING. ROLLING GOING. BUT NEVER GOING GOING.

the artist i had met in san francisco, malakami, and a girl from the villa spaghetti, shared our space on the east side of providence. it was the third floor of an enormous house. when malakami saw me staring at the wall he bought a plane ticket to hawaii. he was afraid of me, he said later. he was my friend and had been drawing art to go with my short stories. he was a skateboarder and skeptic, read h.p. lovecraft and was a pinball wizard. malakami was one of those beautiful people who acts harmless. malakami abandoned me, but he’d been working on it for awhile.

when i’d taken him in at the villa spaghetti, we were a pair of nocturnal heathens. i wrote and malakami drew. we went to bars and we broke open the night. then we moved to providence and he became a contrarian and took a step back. he disagreed with me so often it was impossible to talk with him. his patent response to everything was a deflective “really?” and that’s all he’d offer. no thoughts to follow it, just the hanging dismissal, which got to sounding idiotic in its repetition. he didn’t believe anything. “malakami, i saw your girlfriend on thayer.” “really?” “it’s starting to rain.” “really?” “the narragansett police got busted for looking at child pornography – in the police station.” “really?” “i think i need some new shoes.” “really?”

i supposed he thought i was a sell-out to be working as a newspaper reporter. it was too mainstream. he never said it, because he was reluctant to reveal himself, but i sensed his disdain. malakami was ten years younger than me and was a part of that generation which emphasized to everyone that it had given up before it had started. it had dropped out before tuning in. he never said or asked anything about my work. he got me wondering if i was a bigger asshole than i knew i was, not that i could do much about it. i don’t think malakami and his unfriendly slacker friends understood what i was writing. and it seems to me malakami should have known. he’d read my short stories and knew my sensibility. maybe he did know i was accomplishing more than i would have as a slacker, working as a newsroom iconoclast, pushing boundaries and fighting to get stories into print. maybe he didn’t like me chasing corrupt mayors out of town. i expanded the paper’s vocabulary to include words the readers used and appreciated seeing in print. you know, words like “boobs” (barbara eden) and “shit” (norman mailer). i hurt a fascist police chief so bad he traded nine millimeters for .45s and built a moat of silence to keep me out (didn’t work). i had the distinction of being the only reporter dragged into the publisher’s office for a whipping in the last 100 years. i received fan mail and had beautiful stalkers sending perfumed letters and following me to meetings. i won more journalism awards than anyone in the state, awards judged by the maine press association, the arizona press association, and the connecticut press association. these are just the facts. but the publisher didn’t care any more than malakami. i was waging war on his class, his golf buddy who was paying kickbacks to get city contracts. his friends meant more than that during my first year on his paper, circulation went up 30% on my beat. editors said kind things, but to the publisher i was the antichrist. some co-workers who were better telephone operators than writers were jealous, though content in the cowardice that meant job security. they sat at their desks with their noses in their computer screens and their ears to the telephone while i was out in the air with the man on the street – a practice i was bitched-out for countless times. actually, i was bitched-out for hanging with the man in the street for eight years. i nearly lost my job twice because i believed the man in the street knew more than the mayor. newspapers were killing themselves and i felt headed toward extinction.

malakami was the voice of youth and reason in that house. he gained most of his wisdom from comic books. he broke up fast with a sweet, humble and funny, and gorgeous blonde to go out with a self-centered egomaniac who called herself nova. nova came from santa cruz to study sculpture at rhode island school of design. she had a full scholarship. she quickly started a band for herself, called “slippery pork.” malakami was the bass player. nova once asked me “what are your views on art?” she ambushed me with this at 6 a.m. as i was on my way to the toilet. i was not awake and hadn’t noticed her sitting on the kitchen couch. she scared the shit out of me and i nearly threw up on her. malakami stopped coming into my room and avoided me well before i was staring at walls. maybe it was his girlfriend. maybe he was afraid of me in general. maybe he wanted to deny me. i never believed he envied me, but he had an attitude. as artists, we were opposites. he was very controlled, conscious, and obvious, whereas i was barely involved.

once we were on a pabst kick and i bought him a 12-pack before leaving for the weekend. i told him it was for him. when i returned, the 12-pack was still there, untouched. he had to have drunk beer during those two days. the pabst sat for almost a week and then i drank it. within hours, he bought a six of pabst and placed it like a condemnation in the exact same spot in the refrigerator. he didn’t want anything from me. i saw less and less of him. when i got sick, he vanished, then he bought that plane ticket home. i can’t blame him for being afraid now, but at the time i didn’t understand. the truth is a lot of people are afraid of those with an illness, especially mental illness, even people who love what the sick create – which makes them hypocrites.

PEOPLE ARE EASIER TO SEE THROUGH THAN BLINDS AND I HAVE SEEN THROUGH THE INTERSTATE WITH GLASS EYES. PEOPLE ARE EASIER TO JUMP OVER THAN BUILDINGS AND THO I HAVE YET TO LEAP OVER A BUILDING IN ANY NUMBER OF BOUNDS, MY SKELETON IS THE KEY TO EVERY SOUL. MY GIFT IS FINDING LOVE AND EXPOSING ARROGANCE. I CAN MAKE A MAN LOVE ME OR FLEE IN ONE MINUTE. I CAN INSPIRE GENEROSITY AND GENIUS AND SOULS WITH MY EARS.

i considered doctors and hospitals in the yellow pages and then closed the book.

one day i left the house and walked up to college hill. brown university chicks were looking out the windows of cafes. the cars seemed fast and loud. i didn’t like passing people on the sidewalk. i felt them reading me. i wanted to be alone, but i endured the world because i was on a mission. i went into the army-navy store and picked out a down sleeping bag. the guy there asked me where i was going with it and i told him the catskills. he said i would freeze to death. he tried to sell me a warmer bag. i didn’t want it. spring was coming. i wanted the old down one, not the newer synthetic one. i threw it on the fire escape to air out, grabbed a beer and drank down some percocet. i went into my room and closed the door and played my guitar. i chose the 12 books i could live with for the rest of my life, which would go down in a tent in the new york mountains. there was one woman: marguerite duras.

we had a cat named stew who made a night game of sneaking into my room and getting as close to my nose as possible. when my eyes popped open, he’d run – with a copy of balzac’s seraphita close on his tail. stew was my primary source of humor and entertainment. in the morning he would be standing outside my doorway, the line we had agreed upon, trapping me into a game before i made coffee. we had french roast, columbian, sumatra, kona, cabernet, chianti, bordeaux, pabst, bowmore, johnnie walker black, glenlivet, pernod, absolute, tangueray, newcastle, jim beam, and a bowl of percocets and vicadins. we did not have budweiser.

i was writing for the boston globe, the narragansett times, and reuters. i was making enough to pay the rent, put gas in the car and have a car, have a girlfriend, and indulge my weaknesses. which did not mean i could slack because once you’re in, you’re in, and if you stop for a minute, you’re out. i was caught in a never-ending race to produce bird cage liner. i was manic, and i did not feel strong in the head. i was interviewing all manner of humanity, from presidential candidates and actors to the guys lumping fish heads. they were all the same and none of it mattered to me anymore. my thoughts were fractured. i poured booze on the psychic pain and my thinking became scrambled. my way of life was my life and it was failing. a letter came into the paper, critiquing a story. it was hostile and, for the first time in six years, correct. i had written 1,600 stories and had been impervious. i was slipping.

in this third-story flat, stew was reading the tick and malakami was playing his bass before he headed to work at the laundromat. the chick was on the phone. always on the phone. Her social life was competing with my professional life. malakami had argued that we take this chick on to lower our rent. i had argued against it because i knew she would be ignored. when we had found the place, malakami and i were close, partners in a nocturnal cabal, and the chick had really wanted to move in, so i let it go. she didn’t like living with us and i didn’t care. she was a good chick, but she was taking up space with her need to be fucked. eventually she became a lesbian.

i had started back on my horn and was sitting in with a local jazz band. my hearing had become so acute that i started seeing things: i saw the notes when i closed my eyes, c, Eb, f, f#, g, Bb, c , displayed like a map to possibility. notes flashed while i played. i followed them. i had been playing 20 years and this phenomenon changed everything. i was in an altered state, but i was unaware. i saw these visions as a blessing, not a sign of impending hell.

home from a gig, buzzed, i’d find the globe on the machine wanting shit at 10 p.m. we need all you can get on a vietnamese murderer from providence. we want you to go to his house. do you know vietnamese? do you know anyone who speaks vietnamese? how about a professor at brown? oh, and we need it in 45 minutes. i run out the door and track down a street walled in by graffiti and lit up by shattered glass. i find the house the killer had fled from. there are lights on in the kitchen and basement. i knock. i look through the windows. the place is empty. i interview a neighbor walking his rotweiller near the abandoned house. “haven’t seen him in two days.” back home, i call in a description of an empty house and a guy walking his dog – maybe a cop.

NOBODY LOSES HIS MIND, HE LOSES THE ABILITY TO WARD OFF INVASIONS. YOU LOSE SIGHT OF THE MURAL WHILE YOUR HANDS FIGHT THE ABSTRACT INVASION. YOU BECOME A MONSTER AND AN ISLAND. IT IS THE REPLACEMENT OF THE INDIVIDUAL BY THE ALL, A MARTYRED FLIGHT TOWARD THE SOURCE, LOSING ONE LIFE TO BE A THOUSAND.

i had time to work on the short stories i had written in san francisco two years earlier, which was when i first met malakami. then i had been with jess, who was now a year in the past. jess had worked at an insurance company while i stayed home and typed. she made those short stories possible. malakami was a friend of our neighbors’. he visited them one night while jess and i were there. he was with his girlfriend. malakami was dressed sharply in a long black wool coat and did not say a word to jess or i. actually, he did not look at us despite coming through the front door into a living room where there were only four people, his two friends from hawaii and us. he talked to our neighbor, who was sitting on the couch next to me, but did not look at jess or me. they didn’t stay long. my first impression was not good, but i learned he was an artist. jess and i left california and broke up. malakami and his girlfriend broke up and he came east in a tail-spin. our villa spaghetti days began.

jess was now living in newport. i had run into her twice. it was strange to look at her as somebody else’s girl. at an outdoor flea market i watched a new guy demonstrate golf clubs to her. i had never thought of that. one time i saw her and i missed her. we had been through everything together and no other girl would know that journey. the memories seemed wasted without her. i was now with layne, the tall rhode island school of design student with long black hair. layne was a photography major and almost a normal chick. at first, her pedigree and family history seemed to have corrupted her very little. she was irish and she drank well and laughed a lot. her body and her sense of humor made me happy in the beginning. she was also one of the best photographers i had ever met and i brought her out on a story where she compassionately captured peter wolf’s pallor and decay for the world.

HER LONG ARMS AND LEGS MOVED THE BED. UNDER THE SHEETS I WAS RIGID IN THE SUNLIGHT, WATCHING HER SLEEP. SHE CRAWLED ON MY FLOOR, THROUGH MY CLEAN LAUNDRY, LOOKING FOR HER PANTIES, THE SUN BURNING LACE PATTERNS ON THE PINE. IN THE BACK ALLEY, A DALMATIAN NAMED SPOT BARKED AT SATURDAY MORNING GHOSTS. LAYNE’S EYES WERE THE DAWN. HER EYES BLUE LIKE HAVANA, SPECKLED WITH AZTEC GOLD FLAKES. BLUE AND GOLD WHEN SHE OPENED THEM. HER EYES IN THE MORNING SUN, I NEVER WANTED TO LEAVE THEM. WHEN SHE CLOSED THEM, I WONDERED WHAT SHE MEANT. IS IT STILL NIGHT? I WAS ALONE, WATCHING, WAITING. IF SHE WAS BLINKING, I WAS A FOOL. A FOOL, I FELL INTO HER BREASTS. I WAS JUST A MAN IN THE SUMMER OF HIS LIFE, WRITING POEMS ON HER BACK WITH HER BEAUTIFUL FACE IN MY EYES AND HER BLOOD ON MY FINGERS.

layne revealed herself to be very conservative for a liberal democrat. she was a liberal not in favor of proving it: the poor deserved to suffer. i was a-political and didn’t vote, but i knew there were more nobles among the poor and nobody deserved to suffer. layne’s family were millionaires and she had an allowance. she began to live in restaurants and bars. she had been studying art in italy before we met, had lived on wine and bread and simple foods. six months back in america and she was covering herself in bed. she was aware and it seemed to make her eat more richly. i was not nice near the end, but i was losing my grip on niceties. she was naïve in many ways, young and bourgeois. i could not educate fat.

layne used to scream her ecstacy. if people were talking in the kitchen, i’d laugh. i’d laugh until i remembered i was fucking her. the neighbors looked at me like i was slaughtering women in my apartment. layne fit the times. we were together for a lot of wine and a lot of laughs. she had a taste for fire escapes and abandoned buildings and met her father, the former attorney general, for breakfast every sunday morning. she dyed her red hair black and favored black skirts. she was affectionate. her grandfather had been governor so she could talk shop if i had to. she was 21 and her father was trying unsuccessfully to push her into politics. her father seemed wary of me. he knew the disappointment his daughter had coming. i saw that he saw and he saw that i saw him seeing it. what were two gentlemen to do about a scoundrel? i liked her face. i didn’t care for her naiveté, but her instincts were good. our break-up came along after i was losing interest in sex. she didn’t understand. she was young. no sex meant it was over. this was leading to when i cracked up and didn’t want her at all.

i left providence and resigned from the newspapers. a couple months later i called layne from a payphone near the villa spaghetti, the big white rooming house by the beach where malakami and i had lived. i had returned to rest. i was on lithium and other meds and was alright. i was writing and doing what i had always wanted. we talked and she sounded like she believed in me. we made a date for her to come down the following week. she would be in newport over the weekend for her brother’s wedding, so i’d call her monday. when i called layne on monday, she was changed. words like flippant, superficial, indifferent, distracted came to mind. she was not coming down to visit. a weekend with the attorney general had cleared her head. it had been important to him that i was a journalist. now? i was a nobody and worse. shit, i was now a member of the deserving poor! or maybe she had met someone at the wedding? her doorbell rang while we were talking and she went to answer it. i heard a guy. she talked to him for awhile, laughing, talking, a bit too long before she came back to the phone. she said she had to go. there was no warmth. i could have been selling a knife set. it was okay. i was no longer the same. i was reaching out and back for the life of a man who no longer existed.

malakami didn’t stay in hawaii. he flew back to san francisco and got a position at one of the largest banks in america. he rose fast in this bank. he told me about playing football with the bank’s vice-presidents. the skate punk was very satisfied with himself. his rebellion had not been against the banks and rich; he had rebelled because they wouldn’t let him in. two years later he married a young girl with money and a half-million-dollar house on portrero hill. she also had a pretentious name. within 10 years he would be a vice president at wells fargo bank. he’d stepped into the upper-middle class machine and was dazzled by the insulation. one day i asked the artist how usury was treating him and i never heard from him again. i had believed in malakami, but i think i was just believing in youth.

HE MUST BE DRUNK. BUT IT DOESN’T SHOW. HE PACES HIMSELF LIKE A GOOD DRUNK. THE BOTTLES ARE THE FOOTPRINTS HE’S LEFT BEHIND ON HIS JOURNEY FROM HIS MATTRESS TO HIS MATTRESS. WE ARE SILENT. THE DARKNESS YIELDS TO A STORY. AND LAUGHTER. THEN SILENCE AGAIN. ANTICIPATION DISPLACES THE DARKNESS LIKE A LIGHT BEHIND THE EYELIDS. HE GRABS A BEER AND THE WALLS CLOSE IN FOR A TASTE. I TAKE A DRAG AND LOCATE THE ASHTRAY. WE LIE IN THE DARK. HIDDEN. A SMALL FIRE, A CANDLE. SOMETIMES I BELIEVE THIS COULD GO ON FOR FORTY MORE YEARS. KILLING THE DAYS WITH A SENSE OF OBLIGATION. FALLING INTO THE ROCK BOTTOM OF THE NIGHT, OUR ONE COMFORT. I DREAM THE NIGHT COULD KEEP US ALIVE. I DREAM THE NIGHT COULD KEEP EVIL AWAY. I DREAM THAT IN THE DARKNESS OUR NAKED VOICES BECOME THE COMPLETION OF AN IMMORTAL CIRCUIT. MAYBE THEY DO. BUT IN THOSE PAUSES, THOSE SILENCES, I AM REMINDED OF WHAT WE CANNOT CHANGE AND MY EYES BURN WITH HELPLESSNESS AND SHAME.

Leave a Reply